I used to believe that all I needed to understand the Bible was the Bible itself and Strong’s Concordance. I remember being given a Strong’s Concordance from my dad when I was in my teens. And through the years, I’ve seen many newly baptized Adventists receive baptismal gifts, including a KJV bible and a Strong’s Concordance. I was convinced, and I believe many Adventists are convinced as well, that I could unlock the full depth of God’s word with these two resources. After all, if I could look up the original Hebrew and Greek words using Strong’s, wouldn’t that give me an accurate interpretation of Scripture? It seemed like a solid approach—until I realized how often I was misinterpreting passages, making assumptions based on incomplete information, and falling into common exegetical traps. The deeper I studied, the more I saw the limitations of this method and the dangers of relying solely on a concordance for biblical interpretation. The more I learned solid methods and tools to hold Scripture in high regard and let the text say what it was designed to say, the more inconsistencies I saw in the Adventist Theological framework. (Why I Left Adventism)

I remember a phrase from my dad that is seared in my mind. Several years before leaving the Adventist church, he told me,

“Mike, be careful you might study yourself out of the church,” said my well-intentioned father.

This is a scary reality for many Adventists. I think this fear prevents well-intentioned Adventists from learning solid study skills and asking important questions about the text. Let me explain why the KJV and Strong’s Concordance are so dangerous in biblical studies.

The Influence of the KJV and Strong’s Concordance on Adventist Theology

The King James Version (KJV) and Strong’s Concordance were pivotal in shaping Adventist theology, mainly through the Millerite movement. William Miller, the movement’s founder, relied heavily on the KJV and a concordance to interpret prophecy. Miller predominately used Alexander Cruden’s Complete Concordance to the Holy Scriptures. Miller believed that the Bible could be understood without external theological sources, leading him to develop a historicist method of interpretation, tracing word meanings and thematic links throughout Scripture. This method led him to conclude that Daniel 8:14’s reference to the “cleansing of the sanctuary” pointed to Christ’s return in 1844. The Great Disappointment that followed demonstrated the dangers of misinterpreting scripture based on word studies alone without considering the historical, linguistic, and theological context.

Even after the Millerite movement fractured, Adventism continued to rely on the KJV and a concordance. The movement developed distinctive doctrines, such as investigative judgment, Sabbath observance, and health reform, based partly on the belief that scripture could be understood with a straightforward reading aided only by a concordance. However, this approach has contributed to interpretive errors that persist within Adventist theology. Today, most Adventists are taught to use the KJV and Strong’s Concordance; therefore, I will use Strong’s Concordance for all Concordance references.

Adventist Interpretive Errors Stemming from this Method

1. The Investigative Judgment (Daniel 8:14) – Additional articles can be found here on this topic

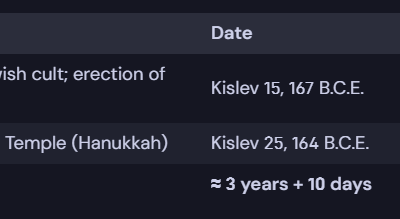

Miller’s interpretation of “cleansing the sanctuary” relied on word studies from a concordance but lacked a contextual understanding of Hebrew sanctuary imagery. This misreading led to the development of the doctrine of the Investigative Judgment, which teaches that Christ began examining believers’ records in 1844. However, biblical scholarship and historical context indicate that Daniel 8:14 refers to the restoration of the Jewish temple following its desecration, not a heavenly judgment process.

2. The Perpetuity of the Sabbath (Exodus 20:8-11) – Additional articles can be found here on this topic

Adventist theology emphasizes the Sabbath as an eternal moral law. While Strong’s Concordance helps trace “Sabbath” throughout the Bible, it does not account for the covenantal shift in the New Testament. Passages like Colossians 2:16-17, which describe the Sabbath as a shadow of things to come, are often interpreted with a narrow focus on individual word definitions rather than their broader theological meaning.

3. Soul Sleep (Ecclesiastes 9:5) – An extensive look at this topic can be found here

Adventists reject the traditional Christian teaching of an immaterial soul, using verses like Ecclesiastes 9:5 (“the dead know nothing”) as proof. Strong’s Concordance defines “know” simply as “having knowledge,” leading to the assumption that the dead have no consciousness. However, this fails to consider apocalyptic and New Testament passages that describe conscious existence after death (e.g., Luke 16:19-31, Revelation 6:9-11).

4. The Identity of the Beast and Sunday Laws (Revelation 13:16-17) – Additional articles can be found here on this topic

Adventists have long taught that the “mark of the beast” represents future Sunday legislation, citing Strong’s definitions to support the connection. However, this interpretation is heavily influenced by their theological framework rather than Revelation’s historical and literary context. Most biblical scholars recognize that the “mark of the beast” had immediate implications for the first-century Roman Empire rather than a modern law enforcing Sunday worship.

The Surface-Level Nature of Strong’s Concordance

At first glance, Strong’s Concordance seems like a powerful tool. It assigns numbers to Hebrew and Greek words, allowing anyone to look up a definition. However, I didn’t realize that these definitions are often just glosses—short, oversimplified meanings that lack context. For example, when I looked up the Greek word logos (λόγος), I saw that it could mean “something said,” “reasoning or motive,” or “account.” (Among several other options) But what Strong’s didn’t tell me was how this term was used in different contexts.

In John 1:1, where it says,

“In the beginning was the Word (logos), and the Word (logos) was with God, and the Word (logos) was God.” (John 1:1, ESV)

…the term logos carries a philosophical and theological weight that Strong’s alone doesn’t explain. I needed a lexicon like BDAG (A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament) to fully grasp how logos was used in the ancient world.

The Problem of Ignoring Grammar and Syntax

Another major issue I encountered as I dove deeper into Biblical studies was that Strong’s doesn’t analyze grammar. Biblical languages have many different grammatical features that dramatically affect meaning.

These insights into Grammar and Syntax challenges are not exhaustive but aim to share some key points. I encourage you to explore the complexities of the Bible’s original languages and the neighboring nations of Israel. (While the following examples are a little ‘Bible nerdy,’ I hope they uncover some of the challenges of the Biblical languages.

These include:

- Aspect (Greek & Hebrew)

-

- More than just tense (which relates to time), aspect describes how an action unfolds.

- Example in Greek:

- Aorist (undefined action) – “He wrote a letter” (simple fact).

- Imperfect (continuous action in past) – “He was writing a letter” (ongoing).

- Perfect (completed action with present effect) – “He has written a letter” (it’s still relevant).

- Voice (Greek & Hebrew)

-

- Indicates who is performing and receiving the action:

- Active: The subject does the action (e.g., “John teaches”).

- Middle: The subject participates in or benefits from the action (e.g., “John teaches himself”).

- Passive: The subject receives the action (e.g., “John is taught”).

- Indicates who is performing and receiving the action:

- Gender and Number (Greek & Hebrew)

-

- Gender (Masculine, Feminine, Neuter) affects agreement and can provide theological insight.

- Number (Singular, Dual, Plural) changes meaning:

- Hebrew has a dual form (e.g., ידיים yadaim = “two hands”).

- Greek distinguishes singular and plural, affecting interpretation (e.g., “you” singular vs. “you all”).

- Word Order and Emphasis

-

- Greek and Hebrew don’t rely heavily on strict word order (like English does), so word placement often shows emphasis.

- Example in Greek: Romans 1:16 (ESV)

οὐ γὰρ ἐπαισχύνομαι τὸ εὐαγγέλιον·

“For I am not ashamed of the gospel“

The expected word order would be “I am not ashamed of the gospel” (SVO – Subject – Verb – Object). But Paul front-loads “not ashamed” (οὐ ἐπαισχύνομαι) to make a bold declaration of confidence. Without understanding the original language, we might miss this and come to a conclusion that the original language isn’t saying.

- Particles and Conjunctions

-

- Small words (like ναί, δέ, γάρ, כִּי, לָכֵן) dramatically impact meaning by:

- Connecting ideas (e.g., “for,” “therefore,” “because”).

- Adding contrast or emphasis (e.g., “but,” “indeed,” “verily”).

- Example: Greek ἵνα (“so that”) can indicate purpose or result, impacting theology (e.g., John 3:16).

- Small words (like ναί, δέ, γάρ, כִּי, לָכֵן) dramatically impact meaning by:

- Imperatives and Cohortatives (Commands and Requests)

-

- Greek has imperatives for direct commands (e.g., “Go!”).

- Hebrew has cohortatives and jussives, which express desire or permission:

- Cohortative: “Let me go” (אֵלֵךְ).

- Jussive: “May he go” (יֵלֵךְ).

- Definiteness and Indefiniteness (Greek Article vs. No Article)

-

- Greek has a definite article (ὁ, ἡ, τό) but no indefinite article (like English “a” or “an”).

- Absence or presence changes meaning:

- “The Word was God” “The Word was a god” (John 1:1 – debated based on grammar).

- Hebrew Verb Forms (Not Just Tense, But Action Types)

-

- Qal (simple active) – “He wrote.”

- Niphal (passive/reflexive) – “He was written.”

- Hiphil (causative active) – “He caused to write.”

- Hithpael (intensive reflexive) – “He wrote for himself.”

- Figurative and Idiomatic Expressions

-

- Some words or phrases don’t translate literally:

- Hebrew to “uncover the feet” = idiom for sexual relations (Ruth 3:7).

- Greek “harden the heart” = stubbornness.

- Some words or phrases don’t translate literally:

- Semantic Range (Multiple Meanings for One Word)

-

- Hebrew שָׁלוֹם (shalom) = peace, well-being, completeness.

- Greek λόγος (logos) = word, reason, message (John 1:1).

These elements significantly impact interpretation, so understanding them prevents misreading Scripture and deepens theological insights. These features are something that Strong’s Concordance cannot help the Bible student understand.

I once assumed that the Greek aorist tense meant a past action, but I later learned that it can indicate an undefined action, which can change theological implications. For example, in Ephesians 2:8-9

“For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast.” (Ephesians 2:8–9, ESV)

Here, the phrase “have been saved” is in the perfect tense, meaning it describes a completed action with ongoing results. Strong’s couldn’t explain that nuance, which meant I was missing out on the richness of the text.

I no longer rely solely on Strong’s Concordance for biblical interpretation. While it remains a somewhat helpful tool, it is insufficient on its own. Furthermore,

I would be cautious to listen to any interpretive conclusions from someone who only uses the Bible and a Concordance. They may sound intelligible, but their Biblical language understanding is lacking, so their conclusions can and often will be flawed.

The Bible is an ancient sacred text that requires careful handling. Incorporating lexical, grammatical, historical, and theological resources into my study gave me a deeper and more faithful understanding of Scripture. My journey has taught me that honoring God’s word means studying it with diligence, humility, and the right tools. I now see the Bible more clearly—not through the narrow lens of a concordance, but through the rich tapestry of historical and theological truth.

As We Bring This To A Close…

When it comes to studying the Bible, I believe relying solely on the King James Version (KJV) and Strong’s Concordance is not the best approach, especially for serious theological or linguistic analysis. Here’s why:

- The Limits of Strong’s Concordance

I see a lot of people using Strong’s Concordance as if it’s a lexicon, but it’s really just an index that links English words in the KJV to Hebrew and Greek root words. The problem is that many assume that looking up a Strong’s number gives them the deeper or authoritative meaning of a word. This method ignores context, grammar, and proper lexical study, which are essential for accurate interpretation.

- The KJV’s Linguistic Shortcomings

I appreciate the KJV’s historical value, but I also recognize that it’s based on Textus Receptus, which is not the most reliable representation of the earliest biblical manuscripts. Because of this, I encourage people to use multiple translations and, when possible, engage with the original Hebrew and Greek texts rather than relying only on the KJV.

- The Dangers of Word-Study Fallacies (Here is a more extensive article on this topic)

One of the biggest mistakes I see is “word-study fallacies,”—where people assume that every use of a Hebrew or Greek word carries all possible meanings. But language doesn’t work that way. The meaning of a word is determined by context and syntax, not just a Strong’s Concordance entry.

- A Better Approach: Original Language Study

I strongly recommend using proper linguistic tools, scholarly lexicons, and interlinear Bibles instead of depending on Strong’s Concordance alone. Learning even the basics of Hebrew and Greek can dramatically improve your understanding of Scripture. And for those who don’t have the time to study the languages in depth, tools like Logos Bible Software provide much better insights than Strong’s.

- The Importance of a Supernatural Worldview

Beyond just linguistics, I believe a proper understanding of Scripture must include its supernatural context—especially the divine council worldview, which is often overlooked. A surface-level approach using only the KJV and Strong’s won’t reveal the deeper themes and interconnections present in the biblical text.

Final Thoughts

I’m not saying that the KJV or Strong’s Concordance are useless, but they shouldn’t be treated as the final authority for serious Bible study. If we genuinely want to understand what Scripture is saying, we must engage with context, grammar, and historical linguistic scholarship rather than relying on outdated tools and oversimplified word studies.

In Christian Love,

0 Comments